Curriculum Changes: Is it Hiding History or Looking to the Future?

Students, parents, and teachers share their views on changes to the secondary curriculum.

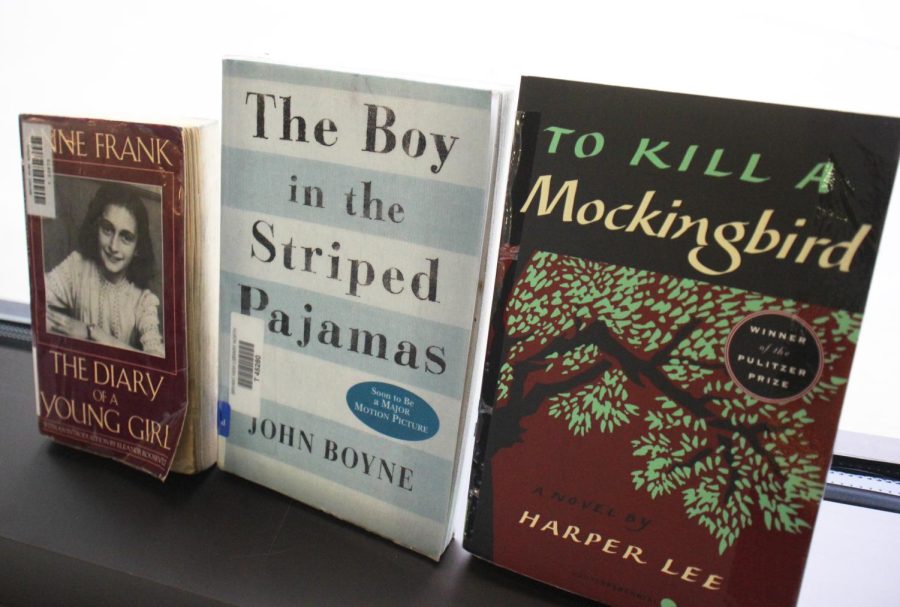

Literary classics were replaced by new text in the secondary english curriculum.

March 28, 2022

When online rumors began circulating of the Bryant School District banning books as part of the recent changes to the secondary English curriculum, many parents and students expressed concerns about censorship. At a school board meeting on February 17, Assistant Superintendent Dr. Angie Dischinger addressed the rumors. According to Dischinger, some texts in the curriculum have been replaced, but no texts have been banned.

“While this is a nationwide conversation happening across many states in our country, it’s not true for Bryant,” Dischinger said. “When a book is banned, it’s removed from the library and it’s unavailable for people to read. So while we’ve undergone a curriculum review and seen a significant change in our secondary English curriculum, nothing has been removed from our libraries, at any of our schools.”

Dischinger explained why the district felt the need to change the secondary English curriculum.

“We needed to ensure that students were engaged in rigorous coursework that’s appropriate for their grade level,” Dischinger said. “As a district, we wanted to provide our faculty and our students with a standard of rigor, a balance of themes and genres, and appropriateness for formal classroom setting, as well as age.”

Some of the texts that were replaced include books such as “To Kill A Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” by John Boyne, and “The Diary of Anne Frank” by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, which is a stage adaptation of “The Diary of a Young Girl” by Anne Frank. While these books have been removed from the secondary curriculum, they are still available in the school libraries for students to read.

According to Dischinger, “To Kill A Mockingbird,” which was previously taught in ninth grade classrooms, was replaced with a unit centered around nonfiction texts by authors such as Malcolm X, Malala Yousafzai and Elie Wiesel.

Two novels that were previously taught in seventh grade, “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” and “The Diary of Anne Frank,” were replaced by “Four Perfect Pebbles,” which is a true story written by a Holocaust survivor. According to Dischinger, the two texts were replaced so that Bethel Middle School and Bryant Middle School would have the same required reading. Along with the replacement of some texts, the curriculum changes also removed certain topics from the curriculum, such as suicide.

“For the purpose of consistency and organization, criteria for text selection was developed by a team of building and district administrators, as well as specialists. This criteria include some district non-negotiables for texts that include racial slurs, graphic sex scenes, extreme violence, and suicide that’s not age appropriate,” Dischinger said.

Although the district says that these themes are inappropriate for a formal classroom setting, some students, such as freshman Amelia Johnson, think it’s still necessary to learn about them.

“To me, these pieces of literature are critical to students’ understanding of things that have happened in our past,” Johnson said. “Some of them could make you feel a bit uncomfortable, but that’s how you’re supposed to feel. Being exposed to stories like these, bit by bit, in a safe classroom environment helps students to be educated about the past and prepared to make a better future.”

Johnson had the opportunity to read both “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” and “The Diary of Anne Frank” in class when she was in 7th grade, before the curriculum was changed.

“Before ‘The Boy in the Striped Pajamas,’ the Holocaust seemed like a distant idea that, while horrific and unprecedented at the time.That book opened my eyes a bit,” Johnson said. “I believe that the up-close view of what it was like provided more perspective on the topic. Reading a carefully-built fictional piece about two children facing that kind of threat was like a shock to my system.”

Johnson said that the school district should have taken students’ opinions into consideration and that many of her classmates agree with her.

“If the administration had taken these views into account, they might have realized how much damage is being done. Changes regarding the future are necessary, but changes erasing the past are immoral,” Johnson said.

Johnson’s mother, Allison Johnson, also thinks that these texts should be taught in schools.

“So many people from different generations believe reading these texts is undeniably profound. These books have stood the test of time and deserve a unique place in our educational system,” Allison Johnson said.

Both Amelia Johnson and Allison Johnson agree that storytelling is a powerful teaching tool.

“Human thought is only as complex as we allow it to become through experience, discussion, and study. Firsthand accounts of personal experiences within the context of atrocities pulls a reader into contemplating what it would be like to experience that themselves,” Allison Johnson said. “There is no greater teacher of empathy than to walk in the shoes of those that survived.”

Allison Johnson also thinks it’s important that students and parents are involved in decisions regarding the curriculum.

“I am well aware that no decision made by those in charge of the curriculum for Bryant School District will make everyone happy. However, some of the most helpful and influential decisions are made through collaboration with people from all backgrounds and standpoints,” she said. “If parents and students are left out of discussions regarding curriculum, the end result will be directly felt by the very kids and families who will have to live with the results of these decisions.”

Allison Johnson says that the other parents she’s spoken with feel like the district was too secretive about the changes.

“The entire process seems shrouded in secrecy, and there is no place for that in public education, particularly with the excellent administrators and board members we have available to us in the Bryant School District. As a parent, it would certainly put my mind at ease to have transparency regarding how we made it to this point,” she said.

Parents and students aren’t the only ones who were concerned. Some teachers, such as English teacher Shawn Regan, were also worried about the changes. He says that students should be taught about complex topics and not just skills-based learning.

“If we continue to dodge the difficult, we will lack understanding the importance and significance of a text and just promote the basic skills that can be easily taught and tested, without any true sense of being a well-rounded lifelong learner,” Regan said.

According to Regan, not teaching students complex topics can negatively affect their future.

“When we limit students’ access to these texts because they are uncomfortable to read, then we will be held responsible when the generation of students become misinformed, easily offended, reluctant, and falsely confident adults that have been able to remain in an echo-chamber of beliefs that have never been challenged because the opposing voice has never been allowed to be heard,” Regan said.

Regan believes that education is found in tough conversations about polarizing topics, and uses that philosophy in his teaching. He often allows his students to have conversations about heavy topics that stem from literature.

“History and literature cover sensitive topics that cannot be ignored. Not discussing those topics for fear of a negative response is borderline cowardice, and cowardice has no place in education,” Regan said.

M. Pope | Apr 4, 2022 at 9:20 pm

Deeya! This is great stuff! So proud of you!

Deeya Rohant | Apr 5, 2022 at 12:07 pm

Thank you 🙂