Paris Climate Talks

International laws aim for conservation

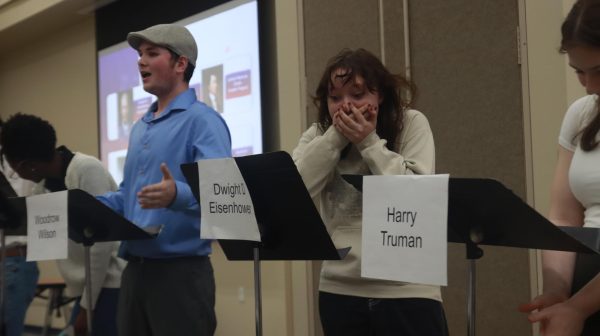

EAST students Oliver Sitepu and James Parada helping the YEA maintain recycling boxes. The YEA team has recently put recycling bins across campus in an effort to reduce pollution. Photo courtesy of Kori Kordsmeier.

February 9, 2016

Delegates from nearly 200 countries convened just outside Paris, France, hoping to set world-governing climate laws. The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) began on Nov. 30, 2015 as an effort to create a legally binding protocol to reduce carbon emissions. The protocol in effect prior to COP21, the Kyoto Protocol, was angled toward developed nations and has been in need of renewal.

The largest component of COP21 set a global warming limit of “well below” 2 degrees Celsius, which means preventing the global temperature from raising more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. The actual temperature raise that global leaders, and many scientists, hope to remain below is 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The resolution has been described by MSNBC as groundbreaking.

The goals have been described by the Washington Post as impossible.

According to the BBC, the world is already at 1 degree Celsius above pre-Industrial times.

“In the last 150 years, our climate has seen a dramatic shift in the climate due to an increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere,” freshman Physical Science teacher Kori Kordsmeier said. “If climate change continues, our planet will continue to see a dramatic increase in climate extremes.”

To keep the global temperature below the maximum set at COP21, both international powerhouses and some of the world’s least developed countries have to make outstanding changes in their fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas production. One of the largest issues within the conference was “Common But Different Responsibilities,” a phrase from the 1992 convention that acknowledges how countries with varying levels of development have different roles in the climate change scene.

Until this point, the United Nations has divided the “rich” and “poor” countries and typically expected more from the “rich” countries. The U.S., along with other world powers, tried to change that during the Paris conference, facing opposition led by China and India, who were advocating for less responsibility for the lesser developed.

The U.S. has taken a stance against climate change and has encouraged lesser developed nations to do the same, yet it has had difficulty in passing legislation preventing climate change.

“[I wish] we had the big government handling [climate change],” sophomore Tatyana Sigler said. “Honestly, I think it should start at paper mills. You know how they have all of those chemicals going in the air from all the stuff they burn? That’d do a lot to help if we just reduced all those gases going into the air.”

The 1955 Clean Air Act outlined emissions limits for U.S. companies and has been added to, but many of its additions have faced legal hurdles. Congress and state governments have challenged more recent proposals, such as President Obama’s 2013 Climate Action Plan. Critics worry that the plan imposes too much government control on companies without enough state input. Additionally, individuals remain unconvinced that climate change is a problem that needs to be addressed so immediately.

“I think that climate change is more of a natural thing,” senior Oliver Sitepu said. “We do have an effect on it and I do believe in the warming of the planet. But it’s bound to happen. Climate change is just a natural planet thing. That’s probably wrong, but it’s just what I think.”

Others believe that legislation preventing carbon production is the wrong way to go about addressing climate change.

“As a Christian, I know earth wasn’t made to exist forever, but while we are here we are to treat our world with respect, but we should not let politics drive us to act hysterically over the environment,” senior Emma Barnes said. “I do believe ignoring it is dangerous. I think an effective way to handle it is to make it a money thing. [We should] provide jobs [such as] building structures for green energy resources. By doing this, we can improve the more pressing economic issues such as high unemployment, but also improve the environment.”