State of Coronavirus

COVID-19 cases surge worldwide, affecting thousands

March 20, 2020

The novel coronavirus, COVID-19, has infected thousands of people globally ever since the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China. As of March 20, there are 209,839 confirmed cases worldwide with 8,778 deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

In the U.S., there are 15,219 cases with 201 deaths in 50 states including the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

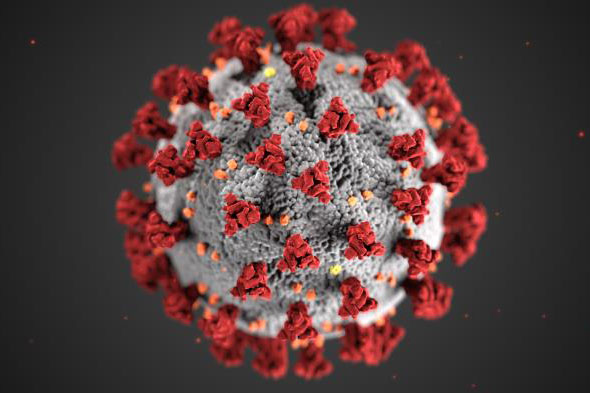

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that contain strains which could potentially cause deadly diseases among mammals and birds. Strains for diseases such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and COVID-19 can cause death among humans.

In 2003, SARS was recognized as the first strain of coronavirus. The first human infections were traced back to the province of Guangdong in China during 2002. Similarly, MERS was identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012, with people displaying symptoms of pneumonia, difficulty breathing and cough.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 8,000 cases of SARS were reported and around 2,000 cases of MERS. In an interview with Vox on Feb. 4, Yanzhong Huang, senior fellow for global health at the Council of Foreign Relations, stated that China learned new precautions after the outbreak of SARS that it’s using against COVID-19 now.

“The main difference is the speed in terms of correctly identifying the etiological [or disease causing] agent,” Huang said. “During the SARS outbreak, the China CDC initially made the wrong diagnosis. They thought the disease was caused by chlamydia instead of the SARS coronavirus. It was Canadian scientists who were the first to correctly pinpoint the virus and sequence it. This time, Chinese scientists were able to genetically sequence the virus in early January.”

Along with quickly identifying the disease-causing agent, China created a reporting system for the community to use during times like these.

“They correctly identified the etiological agent, sequenced it and they shared that info with the World Health Organization,” Huang said. “After SARS, [China] built the largest disease surveillance network with a web-based reporting system in the world. It allows grassroots public health workers to report anything unusual to the central health authorities, the central CDC. [However], that system, unfortunately, didn’t work out this time.”

During the outbreak of SARS, China was accused of covering up the situation and presumably caused the virus to spread further. Recently, China was accused by legal activist Xu Zhiyong of engaging in a massive cover-up of COVID-19 similar to the SARS outbreak. However, Huang proclaims that the central health authorities in both outbreaks faced many issues while attempting to report the cases.

“The local government [in Wuhan] seems to indicate they were misinformed by the central CDC about the seriousness of the outbreak,” Huang said. “But the central CDC seems to indicate they didn’t have the authority to announce confirmed cases–that it was up to the National Health Commission. In SARS, it was also the central leaders who were misinformed by the central health authorities on the seriousness of the problem.”

Huang also believes the authoritarian nature of the Chinese government played a part in the cover-up.

“Authoritarian regimes tend to value secrecy,” Huang said. “The central health authorities at that time were misinformed because of that upward accountability. You’re only accountable to immediate superiors, not to the people who are affected by your decisions. You have that incentive not to tell the truth, to make yourself look good. The concern about the effect on the Chinese economy and tourism, political and social stability–that was a very, very important concern.”

As the coronavirus spreads, so too does xenophobia, the fear and hatred of strangers and foreigners or anything that is strange or foreign. After the major outbreak among the citizens in Wuhan, the notion that Chinese and East Asian people are the carriers of the disease has increased. However, this is not the first time acts of xenophobia have appeared because of a virus. In February of 2014, another virus, Ebola, was occurring in the Western regions of Africa, which triggered travel and immigration restrictions similar to COVID-19. Professor Jason Oliver Chang, associate professor of history and Asian American studies at the University of Connecticut, believes societal reactions to COVID-19 differed from reactions to its counterparts in the same family of viruses in the early 2000s.

“Compared to other viral outbreaks like MERS and SARS, the COVID-19 virus has occurred during a period of intense global xenophobia, as well as anti-immigrant, anti-refugee discourses of racial nationalism,” Chang said.

In an interview with Slate, Chang stated that for around 200 years in America, there was a history of thinking of Asians as “disease carriers.” The belief started around the 1800s when Chinese laborers lived in unsanitary conditions, which resulted in them harboring diseases.

“It’s always been a part of the racial friction, the racial story that people tell about Asians in the 19th century: that they’re the bad apples, the diseases are the result of bad food, bad culture-that it’s an outcome of being racially inferior,” Chang said.

The student health center at the University of California at Berkeley posted a list on Instagram Jan. 31 of the “normal” reactions to the coronavirus, which included xenophobia defined as the “fears about interacting with those who might be from Asia and guilt about those feelings.” After negative reactions, the university deleted the post and tweeted an apology. Although people may see this as a result of panic and ignorance, Chang reckons that this reaction is simply assimilated and continues to pervade pop culture.

“People don’t have to know that they’ve learned this racial story; it’s already a part of how you react, and it shows how pervasive it is in our popular culture,” Chang said.

Not only is xenophobia causing people to reevaluate their actions towards Chinese and East Asians, Chang notes this is also a lesson for Asians to reconsider their reactions towards other races.

“I think this is also a valuable teaching moment to make Asian Americans reflect on their own biases, such as anti-blackness,” Chang said. “Asian American experiences of racial avoidance or micro-aggressions during this time need to be connected to the ways that Asian Americans themselves practice racial avoidance and microaggressions. To be racially suspicious is not exclusive to white people, and it needs to be addressed wherever it occurs.”

According to the World Health Organization, the international community has asked for the U.S. to spend $675 million to help protect states with weaker health systems as part of its Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan. Junior Jackson Bumgarner believes that the U.S. should provide more support in the fight against the outbreak, even after Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced spending up to $100 million to aid China.

“Due to Corona coming to the U.S., it is essentially involved with the fight against the outbreak,” Bumgarner said. “Currently, the CDC is providing updates on the virus constantly, including what is known about the virus, and providing warning on countries that are infected.”

However, Bumgarner believes the U.S. could be doing more.

“Mainly, not cutting the CDC’s budget by a fifth, something which [President Donald] Trump’s proposed budget would do,” Bumgarner said. “If the U.S. wishes to prevent the Spanish Flu Part Two, then the CDC is going to have to have the resources to operate fully. Furthermore, the U.S. has more than enough to support research efforts in other countries, such as ones attempting to use HIV medication as a treatment.”

Although no one knows the eventual impact of the virus, health officials around the world are making it a priority, and Bumgarner is glad that awareness of the illness has increased.

“This conflicting information related to the disease is the thing I truly fear about Coronavirus, as I cannot tell what it is, how it works or even how many people actually have it,” Bumgarner said. “That uncertainty is what makes Coronavirus dangerous, and makes it good that so many are paying attention to it.”

For more information about COVID-19 and latest updates, please see Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Resource Center or World Health Organization COVID-19 Situation Reports.